- Home

- Deborah-Anne Tunney

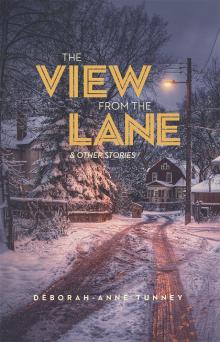

The View From the Lane and Other Stories Page 3

The View From the Lane and Other Stories Read online

Page 3

By the time Margaret died, Joseph had retired, and he and Dorothy were ensconced in their life in Kingston, a life of routine where they shopped on certain days, ate the same meal on Sundays and watched the television most nights. And their lives continued like this, with little variation for more than ten years after Margaret’s death. But one day in December, when they were both in their mid-seventies, Dorothy went into the spare room and saw Joseph sitting on the end of the bed, crying. The street outside the window was dark with an impending storm. “What’s wrong, why are you in here?” Dorothy asked.

“I didn’t know where I was. I thought this was my house on Clement but everything looked different.”

“Well, it’s not, and God knows where you got that idea,” she said, but she was worried, not only by his confusion but she too felt at times as if she were in the rooms of her past. A smell in the kitchen or a sound from the street would remind her of the house on Nelson Street, so that all she had to do was close her eyes, and then sometimes even when she opened them she was still there, transfixed in the upstairs hallway or standing in the kitchen, listening to her mother in the pantry. She would not want to return to the present but wished instead to stay and search for her mother, whom she had not realized she missed so deeply.

In the next year Joseph and Dorothy lived an increasingly insular life, seldom visiting anyone, relying only on their failing perceptions to make sense of their days. Gradually they came to distrust even these, withdrawing from each other, until one night Joseph did not recognize Dorothy sitting up in bed watching the television. He came into the room and demanded, “What have you done to my wife?” and Dorothy, not understanding the question, or his distress, shooed him from the bedroom where she stayed, the television blaring. In search of his wife Joseph drove, still dressed in his pajamas, to the shopping mall close to their home. There he walked the halls until someone called the police who brought him to the hospital.

A few weeks later it was also necessary to hospitalize Dorothy, when she broke her hip in a fall. Their daughter Sophia arrived from England where she had been living, and was alarmed when Dorothy at times did not recognize her and when her father said words she could not understand. Dorothy would lie in bed looking out the window, sometimes silent, sometimes talking about her girlhood on Nelson Street—Sunday dinners when the dining room was crowded with family and friends all talking at the same time, or she would hear the sound of taffeta gowns on the day Margaret was married and June laughing as they rushed down the stairway. When her daughter would leave Dorothy’s room, the memories crowded in again and she would be alone with the slow process of her death. When she did die some months later, Sophia was there beside her. Minutes before, when she had to cough, Dorothy put her hand up to her mouth, the last movement in her life a gesture of courtesy, of decorum.

z

Rita died the same year as her sister Dorothy. For many years she stayed in the apartment building where she had moved after her divorce. After earning his PhD in history, her youngest son moved away to live with a woman Rita could not understand. This woman wore heavy black glasses, her short hair cut in a severe style and she had a habit of looking just to the left of Rita’s eyes when she spoke. Often she would accompany Rita’s son when he came for Sunday night dinner and they would spend the meal discussing world affairs, complaining about dictatorships and fascism, excluding Rita who smiled and busied herself with the meal or tidying up after.

Through those years whenever her children spoke of their father, Rita felt a heaviness in her chest and was compelled to ask questions. How was he surviving without me? was really what she wanted to ask, but in order to counter the look of discomfort she saw on her children’s faces, she learnt to temper her questions to simple enquires about his health, or new residence. Her children said she never really got over his leaving, that it was the pivot upon which all her disappointments revolved, but more and more it seemed to Rita as if her marriage was a story that had not ended, a mystery that remained unresolved.

When she had a bad fall in her early 80s, her daughter arranged for her to move to a retirement home; there she became increasingly quiet and disoriented and by the time of her death she had moved again to a nursing home where she lived for the last five years of her life. By the time of her death she was on the top floor, where patients stayed who never went out and needed constant attention. Her sister June used to visit and they would sit in the sunroom near the nurses’ station. At first, during these visits, they would discuss their children or their own childhoods, but as the years went on Rita usually only answered her sister’s questions with a smile. Often there was nothing to say, and so June would style Rita’s hair, standing behind her delivering a running monologue. “Remember how we used to do this at home and father would get so angry about the hair in the sink?” Combing her sister’s hair, now a pale grey, she would ask “What do you think?” handing Rita a compact mirror. But Rita only smiled up at her without speaking, with a look of soft compliance.

z

June often told her children the story of her father’s death when he was ninety-five. He had lived in Tallahassee with his third wife, a woman of sixty-nine, and the story went that he had walked on the beach and eaten a meal of lobster and crab at a restaurant the night before he was brought to the hospital. He suffered a heart attack and was gone within the day. June would tell this story to her youngest daughter, Amy, and then say how she hoped her children inherited his genes.

But it was June who was blessed with her father’s genes, living into her nineties, still in her own apartment, still reading the newspaper every morning, visiting with her children and speaking to Amy most days. If Amy wanted to please her, she would ask her about her life on Nelson Street, and June would tell her about the clatter from the horses and buggies, the way the street looked in the afternoon when her mother would not allow her and her younger brother off the veranda, or how the high windows in the living room would be left open all night to catch the summer breeze. She would tell stories about her sisters, describing the years when they were young, helping their mother with the dinner and cleaning, working at the Chateau Laurier in their teens and later visiting Margaret at her riverfront home. Amy had heard these stories before, she knew her aunts, had witnessed their lives and was often bored or noncommittal when her mother would begin her recollections. But Amy also knew when her mother spoke of her home how fond her memories were and how she had tried to create the same kind of solid place for her children. Often now as she was nearing the end of her life, when June spoke of her sisters and the years they lived together, a softness would come over her face, a contemplation, the look that let Amy know she was really talking about love.

Aura

Amy entered her parents’ bedroom in the late afternoon gloom of a winter day. She watched her father sleeping. A crucifix hung on the wall above him, with a dried palm from the previous Easter draped over it. Four years old, she had climbed the staircase to see him, after hearing her mother and sister talking about his illness, how he would probably go to the hospital and there was no guarantee what would happen to him there. The room was hot and moist. The sound of her family, watching television or talking with the radio on, was faintly heard in this room filled with the sound of her father’s shallow breathing.

She approached the bed. Barefoot and dressed in a nightgown, she could feel the floorboards under her feet, as frost in a crystal pattern vined its way across the window pane. By his side she looked at his face closed in sleep. There was a glass of water and books on the night table, and on the bed beside him lay the rosary he used every night so that if she would wake it was to the muffled sound of his praying, bead by bead. His eyes opened, flickered and shut, as he retreated to somewhere familiar, the bedroom of his own childhood perhaps, to a dusk like this dusk, when the wind blew cold and he could see the line of light under the door of his parents’ room. Or a spring day with his mother in the fr

ont seat of their car, when she turned her head, lifted her hand to her mouth after a sharp laugh, and looked back to the knitting in her lap.

What was she making, he wondered. It had been a long time since he had seen her this young, and when he looked closely, he realized her auburn hair and hazel eyes made her a pretty woman. In this memory—with the sun beating into the car creating patches of light and dark—he leaned against the backseat window watching the familiar streets of white-trimmed brick houses slide past.

In other moments when the pain subsided—a pain that bloomed so fiercely he was forced to curl around it—he succumbed to the memory of his family during a late summer dinner with his mother at one end of the table, his father at the other. His sisters were across from him, and the baby, his brother, in a high chair beside him. They ate slowly in the heat.

“Mother, I’m going to be in the school concert,” his oldest sister said. The baby looked at her, his eyes wide and deep blue. His mother fed the child with a constant movement from the bowl to his small open mouth, any dribble caught by the spoon.

He slapped the tray of his high chair with an open hand and his mother said, “Be a good boy, no hitting.” They were eating pork chops, fresh beans and mashed potatoes. A basket of bread sat on the table, glasses of milk in front of the children. “What, dear? You’ll be in a play. Well, that’s wonderful.”

Nothing out of the ordinary, this dinner, and yet he often found himself sitting there, his feet not touching the floor, his arms too short to reach the bread basket. The year was 1940, when he was ten years old. Outside a storm approached; the room darkened and thunder rumbled around them as wind, caught in the yard, stirred the air. A branch slapped the back window and his father said, “I must cut that tree, remind me when the weather is better.”

Years later, during a day in early May, he and his mother visited his oldest sister in the hospital after she gave birth to her first child. His mother wore a pillbox hat with a matching veil, a mauve tailored suit and low-heeled shoes the same colour. She looked through the glass at the babies in a line of basinets before the window. “Look at her,” his sister said, “look at her little face.” The baby’s face was puffy and blotched and her tiny hands curled by her head were like unopened buds. His mother tilted her head and said, “Yes, she looks like Sally when she was a baby, but I’d ask the doctors about that rash, that’s not normal.” He heard these words again as if his mother was in the room with him. Had the day really happened like that? His sister and mother with him in the hallway, whispering until his mother’s comment, when they stood silently staring in at the row of swaddled babies.

z

In his uneasy sleep the father returned to the grounds of the sanatorium where he had been confined for TB at the age of eighteen and where he met the woman who would be his wife, the mother of their two children. She was older, widowed, and already had a son and daughter from a first marriage. Now when he would wake feverish, it was her hand he felt resting on his forehead and her care that kept him comfortable, or as comfortable as possible in the widening landscape of his pain. By the early 1950s they had moved from an apartment in New Edinburgh to the house where his son and daughter would grow up, to those yards scribbled with clotheslines and electrical wires and the moving tangles of dogs and children. It was here in the last cold days of 1956, as he slept in an upstairs bedroom, that his daughter came into the room in early evening, and watched the shadows settle in the creases of the blankets, the way mist seen from a high vantage rests in the hollows of valleys and fields.

z

A simple cross above the door, his hands upon the sheets, thin and pale, his rosary in a jumble beside a water glass on the bedside table, the heat, the dull light of dusk filtering into the room, and the young girl standing by the bedside looking at her father. It would be this moment with its distance and their separate solitudes that stays with her. The static room where he lay recalling his life in fragments was the place she moved away from into the rest of her life. The moment came back when she heard the sadness in a violin’s single, elongated note, when a painting touched her with its precise gradient of colour, the rose blush of a bashful cheek or when a still scene appeared before her: a street made black from soft rain, the expanse of the ocean behind the long stretch of beach, snow falling silently before a window. These things of beauty would link her to the moment with her father, when his resting body seemed to glow with a pale aura. His life ended two months later, on a cold, sunny February day in a hospital room; the scenes of his life closed in on him, stopped; his wife and parents standing around the bed, his children half a city away.

Her Mother’s Daughter

Before the mirror my mother arranged the mesh veil of her hat, rubbed her front tooth to erase a smear of red lipstick, and turned her head from side to side to view herself from all angles. It was a Saturday morning in early December 1957 and she was preparing to visit her sister, Margaret, in Montreal in order to attend the wedding of a childhood friend. Sitting in front of the vanity with its triptych of mirrors and assortment of creams and makeup, my mother hummed, tried on different necklaces, and spoke to me about the wedding, the reception, and how she was looking forward to seeing the bride’s gown. We could hear my brother, two years older than me, in the bedroom across the hall, issuing commands to his toy soldiers and making sounds for the explosions. Out the window snow began to fall, the beginning of a storm that would last all weekend. My mother had arranged for my brother and me to stay with our grandparents while she was away. Our father, their son, had died the previous winter and she said it was important that we spend time with them. But I would have preferred to be with my brother and sister, teenagers, the children from my mother’s first marriage, who were allowed to stay at home.

z

That winter, the year I turned five, my mother had begun work as a hostess in an evening club called The Red Door. It showcased singers and orchestras and served steaks and fries to patrons who sat at round tables near the stage. She brought home paper umbrellas for me, the type used to make drinks look festive and I kept them for years, until the paper tore. During this season when it snowed on the duplexes and townhouses where we lived on the outskirts of Ottawa, we were all in our separate ways coming to terms with the deepening meaning of the loss of my father. Winter suited us: the howl of wind, the frost as thick as calluses on the window, the sleet we could see blowing along the icy sidewalks in long, crystal strands, all served to isolate us in our home that creaked under the weight of all that winter snow.

z

My grandparents’ red brick house had white trim and a back yard outlined by spruce and cedar hedges, a yard I remember best in the blue light of a winter afternoon. Nearby streets, parks and school grounds made up a neighbourhood built after the Second World War for civil servants and working class families. They’re there still, those houses, like old women hunched over knitting or mending or some task that forced their concentration inward.

z

I watched my mother leave from the living room window of my grandparents’ house after she dropped us off and spoke to my grandmother in the closed vestibule. Moving into the street, her small form black against the white snow, she turned before entering the car and looked back at the house, frowned and cupped her hand over her eyes as if searching for something against the glare. Years later she confided, “Before I left I had this panicky feeling that I should go back and take you with me, and I always wished I had.”

“Okay, kids, I don’t want you making a mess,” my grandmother said. “So go in the basement and watch TV.” Then she called to my grandfather, “Harry, put the television on for the kids.” The order of her house was a direct result of her unflinching will, her unrelenting routine of scouring, scrubbing, and polishing, and her belief that the uncertainties of life could be tamed by these activities. On her knees with a bucket of hot water before her, she’d wring out the cloth to scrub the fl

oors and walls, a mist steaming from her hands as if they were blessed objects, and surely this was how she saw her quest: divinely ordained, moral in import.

It was the custom that during dinners only my grandparents spoke, usually about the neighbours, the price of food or their other grandchildren. “When Monica was here last week, she was wearing such a smart coat, with ermine trim.” Monica was my cousin, the only child of my father’s sister. “She’s clever, that one. She’s reading her father’s books now, and she loves that show, the educational one, have you ever heard it, Amy? No, probably not.” Although repetitive, my grandmother’s conversations often filled me with anxiety for I never knew when she’d call on me to comment, which she did that night, “Amy, when did your mother say she’d pick you up?”

“Tomorrow, grandmother, after lunch.” We were eating rare roast beef, and I was having difficulty swallowing. A pale smear of pink remained on my plate.

“So. She thinks she can...” she said, looking at my grandfather. When he did not respond she stopped speaking. The sound of cutlery on plates, my grandfather’s dull cough, the radiator’s hiss, filled the silence until she said, “So, I suppose we’ll have to put the Christmas decorations up soon.”

“Yes, I suppose,” my grandfather responded simply. He was a compact man with neatly combed grey hair, who wore a white shirt, suit and bow tie to his job at an insurance company during the week, and a cardigan or vest on the weekends.

My grandmother said, “Amy, I’d wish you stop swinging your legs under the table. Young ladies don’t do that.” She was holding her knife and fork in her hands, her wrists braced by the table edge, her face drained of colour, and her eyes, when I dared to look, were dark points of anger.

The View From the Lane and Other Stories

The View From the Lane and Other Stories